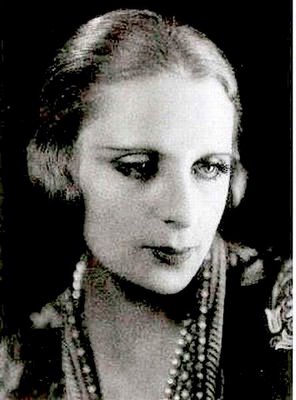

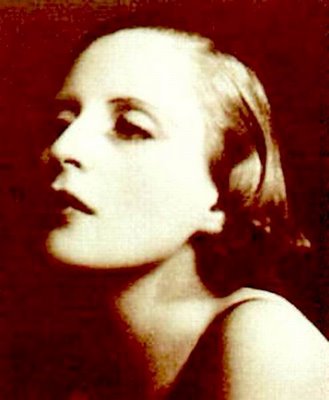

Tamara de LEMPICKA, still a bad girl?

Tamara de LEMPICKA – Not So Controversial Now

Artlover808

Capturing on canvas the spirit of two decades with cool, disconcerting beauty should make the reputation of any artist. But it hasn't worked out that way for Tamara de Lempicka - until recently. For decades, the art establishment has marginalised her. However, the 21st century is fast entering a period of unprecedented wealth and poverty; not unlike the period in which Tamara found herself. Her works which embellished so much decadence of her days is again being appreciated for as such in today’s climate of the nouveaux riches.

Born Tamara Gorska in 1898 to wealthy parents in Russian Poland, by 1919 she'd fled to Paris from revolutionary Russia along with her lawyer husband Count Tadeusz Lempicki. He did not want to work, so De Limpicka decided to take up painting to make money: throughout her life, she would insist that she became an artist through economic necessity. But this wasn't strictly true; since a teenage holiday in Italy - which had given her an appreciation of late Renaissance and Mannerist ideas of classical beauty - she'd felt a vocation to be a painter. She chose her teachers well: from Maurice Denis she learnt the use of simple lines and a smooth finish; from André Lhote, the neoclassical modification of cubism, and Ingres' use of clear, glowing colours, and imperious yet powerful interpretation of the female form and execution of the society portrait.

On the surface, De Lempicka's works look glacial - after all, she is depicting the Jazz Age, the brilliant, brittle society of Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, Arlen's The Green Hat, and Waugh's Vile Bodies. But it's their very appearance - a riot of colour combined with the sharpness of Cubism - which makes them seem to explode from their frames and grab our attention. And it's that particular style which makes us focus on their depth, their humanity.

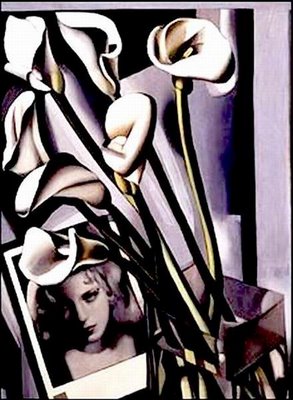

What's especially outstanding? 'The Open Book' of circa 1924, is eye-catching because its conventional subject matter - an open book lying on top of a closed one - shows that she could master the basics of painting, demonstrating her technical expertise, with light and darkness visible on the pages with spot-on accuracy. Her 'Portrait of Prince Eristoff' of 1925 shows the melancholy prince reflective against the backdrop of a Byzantine cityscape - a place of sadness? A place to which he cannot return? Meanwhile, undiminished hauteur - with, maybe, a slight, fatal softness - flits across the features of the subject in 'Portrait of his Imperial Highness Grand Duke Gabriel' of circa 1926. The variable nature of city life appears in two pictures. 'Portrait of Pierre de Montaut' of 1931 shows the efficiency-exuding businessman - with skyscrapers in the background - seeming to epitomise urban hardness. Yet the same cityscape is humanised by the nude in the foreground of 'Nude with Buildings' of 1930. There's little gay about her 'Portrait of André Gide,' of circa 1925, in which the writer squints with apparent cold disgust and for whom the unkind term 'killer fruit' seems apt.

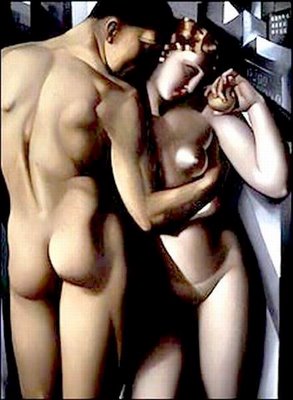

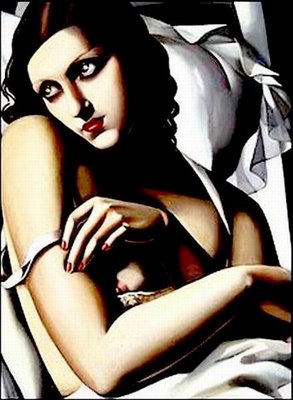

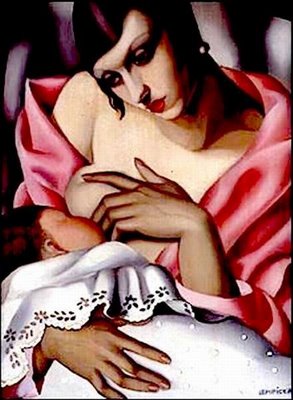

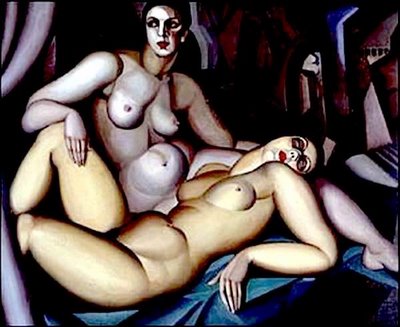

A bisexual woman, De Lempicka's work reflects a glorification of the female form and vignettes of female life. Her powerful, curvy, slab-faced 'Seated Nude' of circa 1923 sets the tone for her depiction of women. Curves and shadows are blended in 'La Belle Rafaëla in Green' of circa 1927 to show her reclining, one-time lover. The booted, square-shouldered subject of 'Portrait of the Duchess de La Salle' of 1925 shows a no-nonsense posture for another of De Lempicka's lovers, with a tough come-hither look that brooks no dissent. 'The Telephone II' of 1930 shows a woman using a telephone, lynx-eyed to ensure that she isn't detected as she - presumably - arranges an assignation.

This body of work should have given De Lempicka a respectable estimation by the art establishment. It didn't. Modernism in all its forms was on the march, presenting itself as both artistically - and politically - correct. It seized the high moral ground inferring that, if you favoured traditional art, you wanted to grind the faces of the poor into the ground. But she used modern forms playfully, and her subject-matter - the nouveaux riches, aristocrats, exiled royalty - hardly fitted the Modernist agenda. She made no polite attempt to hide her desire for social recognition - and money. Also, her celebration of women - including lesbians - may not have exactly commended her to a largely male-dominated art establishment.

After moving to America in 1939 with her new (rich) husband Baron Kuffner, she experimented desultorily with abstract art. She could continue to produce striking work. The exhibition features her 'Escape' of circa 1940 where a woman, clutching a child in a deserted street overshadowed by grey skies, almost melts with fear and misery, capturing with stark simplicity the terror and despair that engulfed Western Europe that year with Hitler's onslaught. This picture should alone have confounded the idea that her work was shallow. It was not to be. Her pre-war career petered-out. Apart from a 1973 exhibition in Luxembourg, only a few small show of her work were staged and she remained sidelined until her death in 1980.

But De Lempicka's exile seems over. There is wide disenchantment with Modernism. People realise that it's just another style, and an unattractive one at that. Her work combines accessibility with deeper meaning. Feminism's emphasis on unearthing sidelined women and their history has played its part, too, in getting De Lempicka into the limelight. The liberation of gay women from dungaree drag has made her the prophetic, in-house painter of lipstick lesbianism.

If the success of the recent Art Deco exhibition at the V&A is anything to go by, this show has the makings of a blockbuster with the added satisfaction of seeing the old self-appointed art establishment experts reaping the fruit of their folly and getting their comeuppance. Most importantly, it will be the vindication of an unjustly-neglected artist who combined beauty with social commentary.

Tamara de LEMPICKA – Aucune Controverse Aujourd’hui

Née dans une famille très fortunée, Tamara de Lempicka a vécu en Russie une existence dorée jusqu’à l’arrestation par les bolcheviks de son mari Tadeusz (de Lempicki), dont elle a fini (après beaucoup d’acharnement) par obtenir la libération. En 1913, le couple fuit la Russie et s’installe en France. À Paris où, très vite, elle fréquente la Haute société européenne et s’affiche femme émancipée et bisexuelle. Tamara étudie la peinture à l’Académie de la Grande-Chaumière (un institut privé). Elle est l’élève d’André Lhote et de Maurice Denis (mouvement nabi) et se passionne pour l’art de la Renaissance italienne et des grands maîtres italiens (Michel-Ange en particulier).

En 1925, elle participe à la première grande Expo Arts Déco (Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels de Paris). C’est à partir de là qu’elle se fait un nom et devient une véritable icône et diva de l’Art Déco et des Années folles. Avec un style glamour tout à fait reconnaissable. « Une lumière à la manière d'Ingres, du cubisme à la Fernand Léger, avec du rouge à lèvres Chanel », résume un critique d'art de l’époque. Elle se sépare en 1928 de Tadeusz, s'installe en 1929 dans son atelier la rue Méchain et, en 1933, épouse le très riche baron Raoul Kuffner de Dioszegh. Tous deux émigrent en 1939 pour les États-Unis (New York, puis Los Angeles) où elle se consacre exclusivement à son art, exposant dans de nombreuses galeries de renom, mais sans plus jamais obtenir le succès qui l'auréola durant l'entre-deux-guerres. Dans les années 1960, elle se tourne vers l’art abstrait. Artiste prolifique, c’est surtout comme portraitiste qu’elle est aujourd’hui reconnue.

Elle s’est éteinte à Cuernavaca (Mexique) le 18 mars 1980, dix-huit ans après le décès du baron Kuffner. Sa fille Kizette, née de son premier mariage, a dispersé ses cendres au sommet du Popocatépetl.

La première grande rétrospective de l’œuvre de Tamara de Lempicka s’est tenue à Paris à la Galerie du Luxembourg en 1972 et a contribué à la réhabilitation de son œuvre (tant soit peu ignorée par la critique qui tenait jusqu’alors son art pour un art « mineur »). L'avant-dernière grande rétrospective de son œuvre (avant celle qui se tient actuellement à Boulogne-Billancourt) a eu lieu à la Royal Academy of Arts de Londres en 2004. Tamara de Lempicka est très peu représentée sur les cimaises des musées français (un beau Portrait toutefois de Tadeuz de Lempicki au musée National d'Art moderne de Paris), hormis le Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes (le premier musée français à lui avoir acheté une toile), auquel elle a légué ses œuvres en 1976 par l'intermédiaire de la direction des Musées de France.

« Rien n’est plus évocateur des années jazz que ces portraits glacés de femmes à la mode et d’hommes séduisants qui jouent au polo dans la journée et boivent des cocktails jusqu’à l’aube », rapporte le critique d’art Frank Whitford, qui rajoute que c’est au cours de ces soirées folles « données par les riches et les décadents, où drogues et alcools étaient servis par des domestiques à moitié nus », « qu’elle sniffait de la cocaïne avec Gide et draguait hommes et femmes », et qu’elle a aussi fait la connaissance de Colette, d'Isadora Duncan, de Jean Cocteau, ou encore de James Joyce.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home