Could this be a lost masterpiece?

Artlover338

Jews are running for their lives in Christie's London showrooms in St James's. A Russian painting called Pogrom hangs just outside the auction room. You can look from the terrified eyes of pogrom victims to a phalanx of bidders discreetly raising hands or catching the auctioneer's eye as he sells exquisite miniatures for rapidly escalating sums. About 15 members of staff stand at desks along the side of the auction, representing telephone bidders. As prices rise, the pogrom victims continue to flee. Tomorrow they too will be under the hammer.

Art is making more money than ever before. This year, a new world record was set for the most expensive painting of all time - and broken a few months later. There is a frenzy in the market that encompasses everything from contemporary art to looted Greek and Roman antiquities. Unexpected discoveries fuel the fantasy that you or I can participate in this greedy sport, that valuable masterpieces lie in attics or cupboards, waiting to be recognised. "A £1m art find behind the spare room door", was the headline in the Guardian a couple of weeks ago after two lost pieces of the San Marco altarpiece by the 15th-century master Fra Angelico turned up in a house in Oxford.

Despite studying and writing about art for more than a decade, I know nothing about the art market. I have never attended an auction before. I have no idea how art makes money. In my hand at Christie's is the new pocket edition of EH Gombrich's classic book The Story of Art. "Actually I do not think there are any bad reasons for liking a picture or a statue," says Gombrich. But the closest thing to a bad reason has to be finding a work of art interesting solely because of the price attached, which is, in sad reality, the main way our culture looks at art. There are only two questions about art we all recognise. But is it art? And if it is, what's it worth?

I am protesting too much. I have been caught in the madness. I am not just at Christie's to observe, but to participate. Today, Christie's also has a sale of European 19th-century art at its other London auction room in South Kensington, which is a little more casual than the grand rooms in St James's. There is no doorman, you walk straight off the street to find the auction in progress in a space crowded with paintings. Here they sell works up to the value of "only" £40,000. In today's 19th-century sale there are no masterpieces, just lots of diverting pictures - Orientalist scenes, battles, landscapes, portraits, the rich variety of paintings the Victorian bourgeoisie enjoyed. But I am not here for the auction. I am here to have my picture valued, and find out if the price is right.

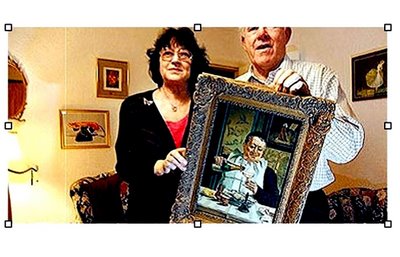

For a while, I had been nursing vague speculations about a painting that hangs in the lounge in my parents' home in north Wales. It previously belonged to a distant relative, Dr Hilda Roberts, an anaesthetist who, as an officer during the second world war, was among allied medical staff who entered the camp at Belsen in 1945. Family speculation has it that the painting may have been a retirement gift.

The first time my mum showed it to me after she inherited it a few years ago, I laughed. I had never seen anything so horrible. It depicts a priest in a black cap eating oysters and quaffing champagne. He is claustrophobically squashed into the scene, in front of an ironically placed picture of an ascetic in prayer. The colours - flat, brownish - are to me charmless. But then, one Christmas when Lord of the Rings was on the telly beneath it, I looked harder. After looking long enough, it did not seem so awful. There was a still life composition in the foreground - bread on a plate, oysters, the crisp tablecloth receding in sharp perspective - that seemed very north European, almost like Dutch still life paintings with their unpretentious details. At the same time, the bluntness of the objects reminded me of the Belgian surrealist René Magritte's metaphysical transformations of still life.

Obviously I did not think it was a Magritte or a Golden Age masterpiece. But I started to wonder if it might not be a 19th-century or early 20th-century work. The subject matter is striking - what used to be called a "genre" scene. The most famous "genre" painter nowadays is William Hogarth, but when Hogarth depicted corrupt Londoners in the 18th century he was adopting this idea from Dutch and Flemish art, which has been portraying everyday life since the days of Pieter Brueghel the Elder. So I was thinking Dutch or Belgian, I was thinking 19th century, and it would not be hard to follow up my hunch because the painting is signed.

The signature appears on a piece of paper propped against a plate on the table: EJ Boks. I googled him, and discovered that Evert Jan Boks was an Antwerp-born 19th-century painter whose most famous work, Surprised, was shown at the 1893 International Exhibition in Chicago and is today in a museum in The Hague. He is mentioned in Van Gogh's letters as a minor star of Dutch art. Boks, in his eyes, belonged in the ranks of success along with Mesdag, Mauve and other artists whose names are only remembered now by readers of Vincent's letters.

Boks specialised in scenes full of comic and satirical incident, in a realist style reminiscent of his Victorian contemporaries. I was intrigued, and wondered if the painting I had found so ugly might be, you know, worth something.

It seemed too odd for that. Surely it could not be what it claimed to be. Anyway, I had better things to do. And money, as I have said, has nothing to do with the pleasure I take in art. I forgot all about it until a fortnight ago when the news broke about the woman who kept two small panels by Fra Angelico on the back of a door in her house until her death. Now the paintings are to go on the market with an estimated value of £1m. I wondered again about the painting hanging in Prestatyn. My curiosity - let me be honest - was balanced between wanting to write a story and being drawn into the money game. So here I am at Christie's with an oil painting under my arm, wrapped up in a plastic shopping bag.

If it turns out to be worth nothing, I think as I wander through the show rooms, it will be about the only valueless object in the world. There is an apparently limitless quantity of stuff awaiting sale. A drawing of the Cat in the Hat inscribed "Best Wishes From Dr Seuss" is expected to sell for £1,500. It is like a local antiques market where you look for nuggets among the bric-a-brac, except the quality of the bric-a-brac is tremendously high. The most ordinary looking table is a neoclassical work from the early 1800s, a dusty book an edition of Cicero dated 1482. The auctioneer does not give a sales pitch about each item, as I had imagined. He simply announces its lot number and starts proceedings. No one registers surprise or emotion as prices shoot up.

The catalogue for this morning's sale of 19th-century European art is as beautifully illustrated as a museum publication, but there is nothing in it about the history of art, just the artist's name, work's title and its estimated value in sterling, dollars and euros. It is a parallel universe to the one I usually inhabit. In a museum, where I would expect to see a painting by the best-known artists here such as Rosa Bonheur, famous in her day for her rural scenes, they would be displayed without a hint of financial value. Here, the price is the bottom line. It makes me wonder: are museums just holding discreet veils over the reality of buying and selling that is art's true existence? More personally, could my painting be in a catalogue like this, if it really is a 19th-century work? To answer that Christie's produces Edward Plackett, its specialist in 19th-century art. I take the painting out of its plastic bag, and put it on the valuations desk. I decide not to share my various theories, but let him say what it is and what it isn't.

When I got the painting from Wales at the weekend, I really did not know what to think. It looked different from every angle and in every light. Sometimes I would look at it and think, "Yes, perhaps it really is by EJ Boks." But what is a painting by EJ Boks worth? Especially one so unappealing in subject and appearance, to my eyes? Then I would look again and think, "No way, it seems wrong. Is the canvas even old? And isn't it odd that the priest has a bottle of Moët et Chandon?" Perhaps I had lost all critical common sense in the fever of money. But I had a great back-up idea. It could be by the 20th-century forger Hans van Meegeren.

A painting by Van Meegeren would be more interesting to me than one by Boks. In the 1930s, Van Meegeren managed to pass off his own paintings as Vermeers - he sold a fake "Vermeer" to Hermann Goering. Van Meegeren made a fascinating candidate if what I had my hands on was a fake. He was Dutch, and in his notorious Vermeer forgery, Christ at Emmaus, which he confessed in 1945 to having painted in order to clear himself of selling a national treasure to the Nazis, he depicts the details of a meal - bread, plates, a glass and a jug on a crisp tablecloth - with a similar combination of precision and clumsiness to the objects in my painting.

I liked the Van Meegeren theory. Then I had another idea, the night before visiting Christie's. Could it be a fragment cut from a larger painting? Could it be a portrait of Boks, with his place name beside him? I looked again at the table, especially its perspective. It was surely a pastiche of the table in Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, which has 13 people sitting at it. Could this be a part of a blasphemous version of The Last Supper? Perhaps its anti-clerical edge was a lot more serious than first appeared. I had to stop myself tearing it out of the frame to find out ...

Luckily I did hold back, because when I display the painting on the Christie's valuation counter, Plackett rather likes the frame. But no way is this a painting by EJ Boks, he says almost immediately, with some disappointment. The painting surface has not aged; there is no significant "crackling". Looking at the back, the canvas is evidently not very old - perhaps mid-20th century. And there are some very clumsy touches to the painting, he says, pointing to that suspect champagne bottle. A pity, because, he explains, Boks - a far more accomplished painter than whoever did this - fetches good prices. If this were an original Boks, he would auction it with an estimated value of £5,000 to £6,000.

It is not entirely unexpected news that this is no Boks, but the surprise is yet to come. What is it worth, I ask through my blushes. Well, if it went to auction at Christie's, it would only be estimated at about £500. This is what I thought it might be worth if it was a genuine Boks. It seems I really am innocent about the market. Why, I want to know, is it worth that? Plunkett thinks it is a 20th-century copy, but a good copy, probably done from an illustration in a book, and with some poor aspects to it - yet, an attractive work that would fetch £400 or £500 for its "decorative" value. So the painting is worth something on the very grounds I would, myself, think it worth nothing. It is valuable for its decorative appearance, when I thought it ugly.

I try my other theory. Could it be a van Meegeren, I ask, half-jokingly? Not good enough, thinks Plunkett. Van Meegeren, after all, was capable of selling his pictures as authentic Vermeers. Obviously he is right. Obviously this was never a Boks. And yet it is worth £500 for reasons that elude me.

I am all at sea, and I still think a mystery clings to the painting. Surely, a copy that has a prominent and false signature is not a copy - it is a fake. Why did someone fake a Boks in the 1940s or 50s? Who would do that? I am not entirely dissuaded from my Van Meegeren notion. Or anyway, I still think there may be a story in this strange object. It is a funny old thing, and no mistake.

The art market is funnier still. I feel strangely elated to have had a painting valued by a renowned auction house, and so to have dipped a toe in the great game of art and money. I go to the big-money auction rooms in St James's. The rooms are hung with paintings that will be sold in the coming days. In a small room are some Old Masters awaiting auction: they too have been valued by Christie's. The estimates are higher, that is all. Here is a version of The Battle of Carnival and Lent by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, estimated at £2m-£3m. A Botticelli at a mere £1.5m. And yet the painting I am still carrying in a plastic bag has been valued by the same auctioneers and has therefore entered, at the lowest level, this magic universe.

Art looks different in the salon of Christie's. It suddenly is not as valuable. In a way, if my ugly old painting is worth £500, nothing can really be quite worth what it is priced at. I have become a bottom-feeder in a boom market. The values I thought were beyond price have a tag in pounds, dollars and euros. It is zeros all the way.......!

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home